In November of 1859, Charles Darwin published ‹On the Origin of Species›, the most influential biology book ever written. Just one year later, he was (temporarily) over it. Tasked with producing the third edition, he instead had become completely engrossed in a new pursuit: dropping meat, dots of milk, and saliva onto the leaves of Drosera rotundifolia – a carnivorous plant that captures prey in its sticky tentacles – and watching it react.

«At the present moment, I care more about Drosera than the origin of all the species in the world», he wrote to his friend, the geologist Charles Lyell, in November of 1860. The obsession proved enduring. In 1880, Darwin published ‹The Power of Movement in Plants›, which detailed how flora do things like climb, fold up, sleep, eat bugs, and follow the sun.

It was one of his least popular books – and unlike his theory of evolution, it failed to budge our general sense of things. Most people still think of plants as stationary. Sure, they may grow, or sway in the wind, we tell ourselves. But movement? That’s for other kingdoms.

But we’re wrong. Plants react to stimuli, search for resources, and send out missives just like we do. And some do so quite spectacularly, fast enough for human eyes to see. A few of our favorite plant movers and shakers are below.

Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula)

Making it Snappy

One of the best-known carnivorous plants, Venus flytraps have special trigger hairs within their paired leaves that help them know when a meal has arrived. If a hapless bug brushes two hairs in a row, the flytrap’s leaves clamp shut. As the prey struggles and bumps more of the hairs, it prompts the plant to start digesting.

Mimosa (Mimosa pudica)

Plant Armadillos

If a mimosa shrinks from your touch, don’t take it personally – they do that to everyone. The slightest brush or shake sends this plant into a defensive posture, curling up its leaves to protect itself from harm. But recent experiments suggest that mimosas can learn to get used to being bothered, staying open despite turbulence if they’re trained to do so through repeated exposure.

Waterwheel (Aldrovanda vesiculosa)

Floating Death Traps

Like Venus flytraps, these plants have leaf pairs that chomp down on unsuspecting prey. But waterwheels lurk in freshwater ponds, and prefer to catch shrimp, snails and tadpoles. Small air sacs suspend their traps near the water’s surface, while long bristles keep debris or other plants away, preventing false alarms. Waterwheel traps snap shut in about ten milliseconds, making them one of the fastest plants on Earth.

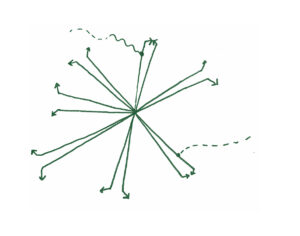

White mulberry (Morus alba)

The G.O.A.T.

For wind-dispersed plants, the farther you can throw your pollen, the better chance your offspring have of finding a place to thrive. This tree’s catkins have stamens that are tightly restrained until pollen release time, when they spring forward with incredible power, throwing pollen at up to 350 miles per hour. This is over half the speed of sound, and approaching «the theoretical physical limits for movements in plants», according to researchers from CalTech.

Common bladderwort

(Utricularia macrorhiza)

Trapper Keepers

Botanists marvel at the intricacies of the bladderwort’s trap. These aquatic plants are buoyed by air-filled chambers called bladders, each lined with trigger hairs. A passing nymph or larva who brushes a hair spurs the bladder to open, sucking in the prey along with a gulp of water. As winter approaches, the bladders let themselves fill up with water, and the plant sinks to the bottom to hibernate.

Sandbox tree (Hura crepitans)

Sharpshooters

It’s very tempting to touch all these plants and see what happens, but please stay far away from the sandbox tree. When its fruits have completely ripened, they explode, sending pea-sized seeds flying at up to 160 miles per hour – nearly as fast as your average arrow.

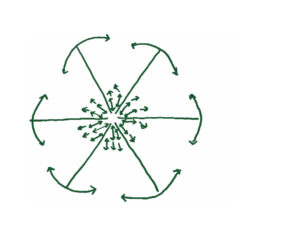

Loasoideae (Nasa poissoniana)

Pollinator O’Clock

Unlike some of the other members of this list, Loasoideae wants to make things easier for bugs – specifically the ones who come to help it reproduce. This plant swings its pollen-tipped stamens from the outside of its flower into the middle one at a time, to make them more accessible to bees. It even schedules these deliveries each day, remembering when pollinators generally come, and tweaking its timing to be ready for them.

Telegraph plant (Codariocalyx motorius)

Mysterious Flaps

This shrub has two sets of moving leaves: small paired leaflets that waggle, and larger leaves that sweep up and down in the same way, but more ponderously, like fans. No one is quite sure why – the plant may be calibrating its angle to the sun to maximize light intake, waving menacingly to confuse would-be predators, or flapping like a butterfly to prevent real ones from laying eggs on it. Or maybe it’s all three.

Starfruit (Averrhoa carambola)

Playing Dead

Some plants, including the starfruit, the mimosa, and most beans, have a special type of leaf base called a pulvinus. This elbow-shaped structure transforms external stimuli into electrochemical signals that spur physical movement by the plant’s larger parts. In the case of the starfruit, a touch causes the plant’s leaves to quickly droop, perhaps making them look less tasty to whatever herbivore was nosing at them.

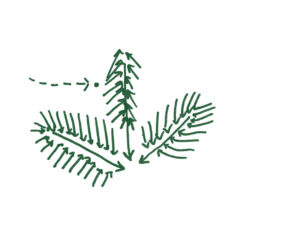

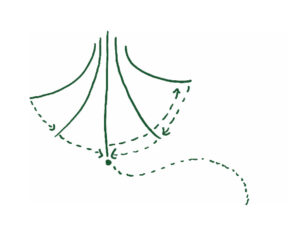

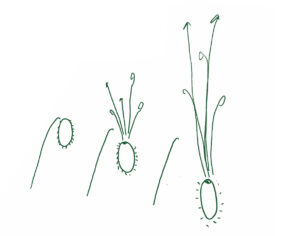

Pimpernel sundew (Drosera glanduligera)

Bullseye Every Time

Each of this sundew’s long green tentacles is tipped with a sweet and shiny sphere of mucus. Any tempted insect who stops for a sip becomes stuck there. As the bug writhes around, it triggers the sundew’s tentacle to snap upwards like a catapult, flicking the bug into the center of the plant, where it is consumed. Can you see why Darwin loved sundews so much?

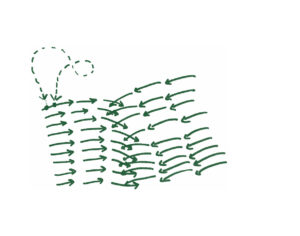

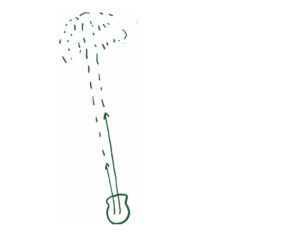

Peat moss (Sphagnum sp.)

Kaboom!

Peat moss is one of our most prevalent plants, covering nearly 1% of the Earth’s surface. Some of its success is likely due to its reproductive strategy. It keeps its spores in tiny capsules, which shrink as they dry out in the sun, compressing the air inside and building up pressure. They then explode into pint-sized mushroom clouds, a shape that helps them ride the wind far distances.

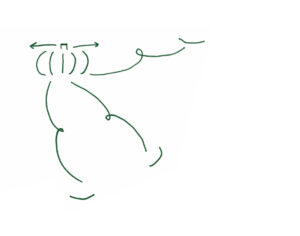

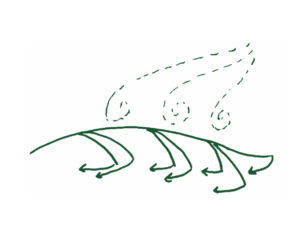

Squirting cucumber (Ecballium elaterium)

Gesundheit!

Squirting cucumbers have spiky fruits packed to bursting with seeds and mucilage. At the slightest touch, the fruits snap off their stems, their slimy payloads erupting out of them as they fall to the ground. It’s a spectacular way to go out.